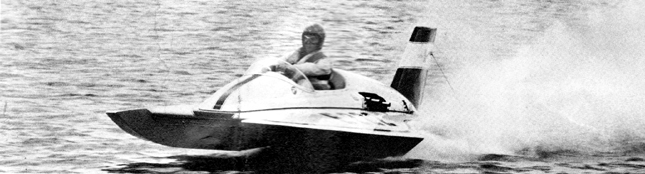

Dave Gill built Vulture,

loosely based the on USA hydro 'Record 7', a Ron Jones

design.

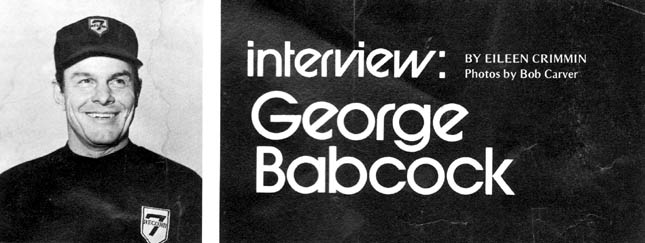

Below is an interview with

the owner/driver of 'Record 7', George Babcock, from

the 1971 American 'Powerboat' magazine.

George

W. Babcock, Seattle businessman, owner / driver "Record 7”

7-litre, owner "Colonel Bogey" 280. Member Gulf Marine Racing

Hall of Fame 100 MPH Club. First Limited Inboard driver to average more

than 100 mph in competition. Babcock and "Record 7" simultaneously

held Divisionals, Nationals and High Point titles, set competition record

of 101.58 mph and Kilo straightaway record of 166.159 mph. His 280 "Colonel

Bogey" holds competition record of 78.466 mph. Yale '51; pilot;

skier; mountain climber; third generation member of one of America's

distinguished business families.

POWERBOAT: Within the short time of two years, George,

you've been elected by Gulf Marine Racing Hall of Fame to their 100

MPH Club and 150 MPH Club. You drove your 7-litre Record 7 to the straightaway

speed record 159 mph for the Kilo, set the course competition record

at 101.80 mph, won the Nationals and the Divisionals, and achieved National

High Point Honors in 1969, then spearheaded your racing team and your

280 Colonel Bogey to a competition record of 78.466 mph in 1970. You

were the first man in Limited Inboard history to average more than 100

mph in competition and, to the best of my knowledge, the first to hold

all five 7-litre achievements simultaneously.... ALL within two years!

This being the case, what have you to say for yourself?

BABCOCK: Just lucky, I guess.

POWERBOAT: Flippancy doesn't account for achievement.

Fast though you are with a quip and a needle it takes more than either

to get so successful a racing combination in so short a time.

BABCOCK: Actually, I'm not that new to racing. I've

had a boat of some sort ever since I was a kid living on the Ohio River

about eight miles outside of Louisville, Kentucky where I was born.

We kids-there were six of us progressed from rowboats to outboards to

inboards. Then the rest of the family went one way and I fell in love

with Typhoon, a venerable George Crouch 40-foot runabout which I restored

and played with until it was destroyed by fire.

Meanwhile, I'd bought the Jack Colcock hull, Challenger, after Chuck

Lyford won the 7-litre Nationals with it. I campaigned it successfully

in the west but never duplicated Lyford’s national laurels. The

effort, however, gave the boat a chance to give me some driving lessons

and a chance to experiment with various driving techniques.

POWERBOAT: Do you remember any particular moment when

you decided to go after all the 7-litre records?

BABCOCK: No. No particular moment but I think it was as a gradual resolve.

I believe the 7-litre class is the top power-to-weight ratio performer

bar none, including the Unlimiteds which, as I never a secret, I believe

are ridiculous in every way.

POWERBOAT: But you sold Challenger. Why?

BABCOCK: It didn’t have the stuff for the speed

records I wanted to set. Challenger at 1,601 lb., with Lyford driving

those 301 little cubes blew off all the big, supercharged competition,

and after we changed to a 327, I won the 1966 National High Point honors,

and during one stretch we put 52 heats under the boat without failure

of any kind. But, as we went for higher speeds using nitros oxide, etc.,

we seemed to be pushing the boat beyond its design limits. I dangled

it more than I should but only dumped twice. Once going too slow, once

because of another boat. Overall the craft held up well and still is

being campaigned as a 266.

But we needed a faster boat. I talked with several designers, investigated

other hulls, even tried one, and finally settled on a Ron Jones concept

in 1968.

POWERBOAT: Why? Or do you keep your development concepts

secret?

BABCOCK: No. I believe racing should be completely

open about its advances AFTER a team has won its goals. Racing would

progress a lot faster if it adopted this policy and we'd all look a

lot more professional. As to my reasons for going along with Ron Jones,

I had this idea that posting a 100 mph heat would require a boat which

could be held reasonably close to the buoy line on the straights and

go through the turns almost at straightaway speeds.

I'd seen Les Brown's Long Gone perform brilliantly at the Orange Bowl,

and I'd seen Ed Morgan's 225 Chipwinder perform as fast as Challenger.

Jones said he had a new design on the drawing board called a "pickle

fork!" This was in 1967, remember. He believed that the reduction

of front lift would enable him to move the CG farther back to place

more weight on the prop and thereby provide more efficiency and better

acceleration. For myself, I wanted to be able to drive harder through

the turns and accelerate smoothly off the exit pin. Where other hulls

would be leaping badly losing time and speed, I'd be out of the turn

and up the backchute before the others quit floundering.

Jones felt he could design toward this driving concept, but also felt

that 1,000 hp, or 850+ foot pounds of torque in the 4,000 to 7,000 rpm

range would be needed to do the power job.

POWERBOAT: So that was the start of it?

BABCOCK:

Not quite. We established four major goals. 1. We would aim at

a 1969 racing year with the boat ready by December 1969 and initial testing

done in California. 2. We would attempt to raise the 1-2/3 mile course

record from 93.072 mph set in 1965 by Bill Sterett to over 100 mph. 3.

We would try to ahow any prospective 7-litre owner/racer that you could

campaign vigorously on the local, regional, and national circuit-about

19 regattas-with one engine and comparative low expense while putting

on as fine a show as the Unlimited Class with its huge trailers of gear,

special equipment, high money expenditures and constant maintenance problems.

4. We hoped this effort would create new interest in Limited Inboard hydros.

Since the Unlimiteds hadn't appreciably altered their speeds, format or

record in many years, and had killed six fine drivers in a relatively

short span of time, it seemed to me tit not enough was being done to develop

interest in the fastest (by power-to-weight ratio), most interesting,

colorful class of inboards, namely, the 7-litres.

To achieve these goals we gave thee power assignment to Keith Black, asking

for 1,000 hp out of a 426 supercharged Chrysler engine using straight

menthanol and no nitro. We gave the hull assignment to Ron Jones with

no restrictions except that it be able to hold the specified engine.

POWERBOAT: And WIN!

BABCOCK: Naturally! No, seriously, we had the hull design

concept in mind, but I feel a good designer most be left reasonable latitude

for possible change during construction, if such change is well substantiated

and not a radical departure from the original agreement.

POWERBOAT: With the hull and power work farmed out what

was your part in all this?

BABCOCK: I coordinated the effort, eventually raced the

boat and put up the loot, which I found from time to time was an important

ingredient when applied properly!

POWERBOAT: In your initial testing, what did....

BABCOCK: Excuse the interruption, but we had one subsidiary

goal pertinent to racers everywhere. We also wanted to prove a belief

of mine that if you approach racing correctly with proper hull design

and proper engine, then exercise proper maintenance and management without

too much hurry and rush, you can put together a team and new concept to

come out a winner. Further, that it could be done with non-professionals.

I flat guarantee we were all amateurs except Jones and Black. And except

for Glenn Davis' gear box design, which MUST be called professional, we

were strictly a bunch of do-it-your selfers! However, we followed one

rule always: When we needed a pro, we didn’t interfere try to bull

it through. We called a pro, didn't interfere, and left him with responsibility

for the work. I believe more amateur teams should adopt this policy.

POWERBOAT: What were you up against competitively!

BABCOCK: Everything tremendous!

But especially Long Gone, Sayonarra, Miss Merton Bluegrass and Earl Wham

who held the Kilo at 159.217 mph, Country Boy, Budweiser, Thunderbird,

Quick Delivery and the rest. These were very quick litres. We heard that

several were unbeatable.

POWERBOAT: Back to initial testing of Record 7; how was

she?

BABCOCK: Loose. Very loose. We made two phone calls a

week to Jones for some time to settle her down. But Jones' premise is

that you can always settle a boat down, but if it's glued and running

inefficiently, it's far more difficult to break it loose and make it efficient

than it is to tame it. The boat sponsor-walked and sometimes there were

two, three feet of daylight under her. It w-as a VERY interesting ride

at times. Also a tremendous thrill. It handled, steered and controlled

much like Challenger, yet was sporting almost twice the horsepower and

had a rear end which seemed never to come down! As you know the secret

with conventional hulls is to keep up the rpm so the tail won’t

drop. Imagine how I felt driving a hull which, slow or fast, never seemed

to drop! Finally, I decided if I could keep the left skid fin planted

in the water and the boat tracking properly, there would be no limit to

the speed attainable in a turn or on a chute. However, initially we were

such an awesome sight that I believe a few delegations were called to

beach us as a hazard to boat racing and everything else!

POWERBOAT: How'd you tame her?

BABCOCK: Jones suggested changing the balance and getting

some air released from under the boat. We trimmed the air traps, eventually

took them completely off. Later we made and did one other thing I won’t

reveal. We fiddled with 8 to 10 other minor things, went out on Black

Lake for an easy run, came in and found we'd averaged 90 mph. I couldn't

believe it. I thought I'd run 80 or less! Next heat we posted a 94+ average,

but a displaced buoy had been returned to the course without a re-survey.

No record possible. However, the engine was torn down anyway-the first

of several times that year we were to take it back home in a basket. But

that's part of record racing.

POWERBOAT: We recall that Record 7 actually broke the

7-litre competition record three times the summer of 1969. Unofficially

at Black Lake with the 94, officially at Green Lake with 97.5 and officially

on Lake Sammamish with the final 101.580 mph. What about all this?

BABCOCK: Well, we were up against Earl Wham and Merion

Bluegrass at Green Lake. Although we broke the clock with a perfect start,

I've never driven a poorer race in my life. I was always three to four

seconds behind the boat. In the second heat we had too much magneto advance

and blew a couple of pistons. Since we were supposed to leave for Nationals

next morning, this was tough. The logistics of getting personnel and engine

and to Morgan City, La., by the following Thursday afternoon were an intinary

nightmare. But we made it.

At Nationals our strategy was merely to finish ahead and not extend the

boat at all. I found the clock difficult to read and that, coupled with

my desire not to jump the gun, found me 7 or 8 in a field of 12. Lord,

I've never seen so many big boats and so much water in my life! In fact,

for half a lap I didn't see anywhere but straight up because ise there

were walls of water all around me. I moved to the outside because all

the thrashing, beating and action was on the inside, and at the start

of lap two I was all by myself, which was gratifying. We won the first

heat.

I was about a second late at the start of heat two, fortunately, because

two of the eight boats jumped. Budweiser, behind on the inside, was moving

well. To offset that situation, I put my foot into it, got just behind

Long Gone and stayed there. And won the National Championship. Everything

went according to plan except that I never want to start late again among

that many boats. It takes more courage than I care to summon up on given

notice. Perhaps I should mention here, too, that officials, in particular

Charlie Strang. watching the start of all these l2 healthy 7-litres, said

they'd never seen anything as thrilling in Limited, Unlimited or any other

racing competition. As is said, strong men paled, women fainted and children

screamed. Or something!

POWERBOAT: Your Lake Sammamish try at the over-100 mph

competition record came at the season end, didn't it, you with no cushion

of extra regattas in case you didn't make it?

BABCOCK: Yes. Ole big mouth here had said publically

we'd try for the record, so the time came when it was put up or shut up.

First we tried a late regatta but had a problem, came back to the pits

on the end of a string and spent the day taking 33mm color pictures!

The next week there was a special drag and ski sanction so we arrived

again primed to go. Water was perfect and as I mentally went over race

strategy I remember thinking that since this was the first day of the

event, and first heat of two days of four heats I shouldn't be too concerned,

and shouldn't press too hard. We'd learned from previous racing that the

needle only had to hit about 135 mph on the chutes even though the boat

could do better easily. But faster speeds wouldn't allow the boat to settle

down to make best usage of speeds through the turns. It's a reverse psychology

that's hard to control when you're driving, but you pour it on in the

turns and actually back off on the chutes-back off from maximum chute

speed possible, I mean.

In the first lap I bettered 100. In the second I posted exactly 100 and

in the third with the boat working perfectly I turned everything on for

the finish to rack up a total time of 2:57.2 for a heat average of 101.580

mph. That last lap was 103.4 mph and I KNEW it was faster than I'd ever

run before. But the speeds truly surprised me because I did not think

I'd run 100 in the first two laps.

POWERBOAT: You showed practically no emotion over this

record. Just threw your arms up once in a big V, then helped get the boat

cranes onto the trailer. Weren't you pleased?

BABCOCK: Yes-no. Not immediately. You see, we'd just

discovered we had racked up enough points to win High Point for the year.

We'd won Divisionals and Nationals. Now we had a new competition record,

and a milestone of over 100 mph at that. We'd toyed with running the Kilo,

too. Suddenly, we had everything except the Kilo and it was sort of overwhelming.

The only thing more surprising than NOT achieving the goals you set, is

achieving all but ONE of them. It's exciting but sobering. And it really

put the pressure on toward running the Kilo. But we DID have a champagne

party and over celebrated handsomely. It was then that I think everybody

really got excited.

POWERBOAT: What was your preparation for the Kilo?

BABCOCK:

Nil. Or practically. What I mean is, our goal was to campaign inexpensively,

without elaborate changes, always utilizing a competition set-up.

POWERBOAT: You mean you ran the Kilo in competition configuration?

You sound nuts!

BABCOCK: That may be, but our idea was to put a boat

into speeds above 170 mph with competition setups and combinations. We'd

seen the Unlimiteds go into special everything to attain higher speeds.

We felt this was both unnecessary and clumsy. We wanted very high straightaway

speeds with a boat still able to return, unadjusted, to circle racing.

And we were determined to get what we wanted.

POWERBOAT:

But you prepared SOMETHING, didn't you?

BABCOCK: We checked everything. The gearbox appeared

to be indestructible. The engine, except for repair of burned pistons,

changed sparkplugs, and some bearing changes through the season was the

same as new. We'd had no difficulties due to routine maintenance on heads,

push rods, or valves. We running the same blower drive set-up. Careful

disassembly and assembly at key times had provided us with an essentially

new engine despite vigorous high speed, high racing.

It turned out that the Seattle Inboard Racing Association was able to

stage a today Kilo Trial Noy. 15-16. We ran a complete checklist on the

entire boat and trailered her to Samamish with a "flight plan"

of starting into the traps at 160 and reached a possible 170-175. In testing

we'd figured a 6.500 rpm with a specific prop pitch gave us a 160 speed.

In our first run through the traps on the top side of 6,500 rpm we posted

160.1 exactly. I was too slow on the reverse run at 148 and got an average

of 154. A pit man held up the chalk board noting 138, meaning 138 mph,

and I felt sunk because I knew dang well I'd been faster-boat feeling,

air pressure, rudder pressure transferred to the wheel. I couldn't believe

it! So I tried another run which averaged 164.9 up and 159 back for an

overall of 161.4, which was a new world's record.

POWERBOAT: But the present record is 166.159. Why did

you up it?

BABCOCK: Earl Wham. About half an hour later, Earl went

through. It was obvious he was capable of surpassing our 161. We also

knew Tom Gilpatrick's Quick Delivery could go through like it was on a

rail and post a speed above our 161. Remember, this was Saturday, and

each team had time to make modifications and come back Sunday to blow

off my record. We huddled. Yep. We'd try again. And we decided to take

a look at 7,000 rpm.

On our first run I know I entered the traps at 160 or more and somewhere

in that run I believe we hit 180. A patrol boat held up a boat with 72

on it, meaning I'd posted 172 mph. That was gratifying-to post 171.983

mph actual timed speed at 7,000 rpm. Coming back I got into the traps

slower, didn't get through as fast and had one dipsy-doodle at the end

as I decelerated. But we had the new record 166,159 mph on Nov. 15, 1969.

POWERBOAT: Care to give out any technical information?

BABCOCK: Sure, because that leads into the subject of

trying for the world water speed prop-driven record of over 200 mph. We

used two props all year, a record 12 ½ /18½ and a Record

12 ½ / 19. We used the 19 for the Kilo. Fuel was standard menthanol.

Gearbox ratio, which is 60% overdrive, was the same. Used the Indy ignition

system, the infrared without breaker points. We knew the engine was rated

to develop an undisclosed maximum horsepower, with 1,000 coming in at

7,200 rpm supposedly, we were to red line it at 7,500. But with so much

throttle left after 7,000 I’d guess the engine would turn 8,000.

Keith Black says that’s a no-no. After 7,500 not only are you loosing

power but at 8,000 rpm the engine won’t live long. However, we do

believe we could turn an engine, gearbox and prop set-up at 8,000 which

would give us a theoretical speed of 194 mph at the same slippage factor

on the prop evidencing at 7,000 rpm. We found slippage decreasing after

160 mph. We got 20% slippage at 5,000 rpm; 18% at 5,500; less than 15%

at 6,000 and under 12% at 7,000. Assuming about 10% at 8,000 leads us

to a 194 speed. A change in gear box ratio to 60% or 70% overdrive, and

a prop change front 19" to 20" pitch and we'd be in the neighbourhood

of Roy Duby's over 200 mph set in the Miss U.S. unlimited.

POWERBOAT: As we all know, your attempt at this higher

speed with the late Tommy Fults at the wheel was unsuccessful.

BABCOCK: Yes. We had problems. Then the boat took on

water and became unbalanced in the final run that ended in an accident

which destroyed the boat and injured Tommy. Fortunately, not seriously.

POWERBOAT: Do you think the rather astonishing accumulation

of the five 7-litre titles and records may have affected your usual cautious

appraisal of record-setting chances?

BABCOCK: When

I look back now I think we were premature. I still think the boat, engine,

rudder, gearbox, and all-this concept is capable of a world prop-driven

record. Now, at this higher speed I don't know if a competition configuration

boat is usable. Maybe even a boat in straightaway configuration isn't

usable, either. It may be that a special boat and special set-up is required.

I don't know. I don't think anybody really knows, yet. Those extra miles

up in that speed range are mighty hard to come by. But our idea always

is to TRY for speed with competition configuration.

POWERBOAT: The loot you mentioned-what did it all cost,

George?

BABCOCK: Our pioneering effort cost about $35,000. But

another litre could duplicate our situation, using what we learned, for

around $20,000 a season. We're willing to tell anybody the concepts we

used. And we'd be DELIGHTED to tell everybody what they DON'T need. We

had spares and duplicates we never used. Also, both Keith Black and Ron

Jones got experience at our expense which doesn't have to be duplicated

now.

POWERBOAT: We understand you had a new Record 7 built

and it's now being outfitted. Which reminds us that last year your 280

Colonel Bogey raced and set a new competition record of 78.466 mph with

Pat Berryman driving. How come you didn't drive?

BABCOCK: I'm beached for business reasons.

POWERBOAT: What

attracted you to the 280 class?

BABCOCK: Competition and difficulty. In many ways setting

a stock record is tougher. Fortunately, we had Orv Roupe of Precision

Engine Specialists, Inc., Seattle., interested in the 273 Plymouth. He

worked on three of these engines which ultimately achieved only a 7 hp

variance on the dyno. But the one in Colonel Bogey did the job. Earl and

Quentin Rue worked with Orv on the allowable modifications in lubrication

areas, exhaust system, valve spring tensions, cam shaft settings, carburetor

and other settings and all allowable tolerance throughout the engine.

POWERBOAT: Since you've had success with both stock and

modified engines what, in your opinion, sets apart the stock specialists?

BABCOCK: Obviously, the stock hull must be more efficient,

and whoever works the stock engine must be super-expert. In our case,

Orv Roupe and his men are deeply knowledgeable about the science and physics

of the internal combustion engine. Their attention to detail is minute

and patient. But one real secret is that they forbid additional tinkering

with the engine by boat crew, self-styled experts, other mechanics, owner

or anybody! In plain words, they won't tolerate an amateur screw-up of

their professional work. Which is quite bright of them.

POWERBOAT: Looking to the future, are you going for more

280 records?

BABCOCK: Yep. Hop to raise our 78.466 mph to around 80

or more. And we think about the Kilo 280 record, too, at 110+, perhaps

even up to 115 mph.

POWERBOAT: What’s slated for this new Record 7

in the competitive area, or Kilo?

BABCOCK: First we have a new, but veteran, driver for

Record 7 in George Henley. He's proved himself in outboards, limiteds

and unlimiteds. He'll work with us to see what the potential of this new

7-litre is. We're hoping to see a 105 mph average on the course. If we

can get that, then we may have discovered a format for a new combination

which will provide a breakthrough toward even higher speeds. This will,

in turn, provide proving grounds for the next step toward a higher state

of the art of racing, which we hope will be applicable to racing in all

the classes. For ourselves, the right sponsor might see us competing in

one of these classes. As for another Kilo run, we have no plans toward

it and no desire for a higher Kilo speed at this time out of the 7-litre.

POWERBOAT: Those sound like a fair batch of goals which

will keep you busy this season, possibly several seasons. What's in the

immediate future?

BABCOCK: We're aimed at both the 7-litre and 280 National

Championships with present plans, but the national economy always has

something to do about whether we manage to appear or not.

POWERBOAT: What? You mean the availability of money has

an effect upon racing, as well as the skill, management, determination

and so on?

BABCOCK: Did I say that? Certainly not. I never said

that. Like I said earlier, it's luck, pure and simple. We're just lucky,

that's all!